In the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.

Dear brothers and sisters, forgive the briefness of these words sent to spare our tired Father Mark having to write a homily after his travels and demanding week.

Our Gospel reading today begins with the question that is the very reason for the Saviour preaching His parable of the Good Samaritan: “Master, what shall I do to inherit eternal life?”

Sadly this was not a sincere question, but a prideful and crafty attempt of a young pharisee to entrap the Saviour, and elicit an answer at odds with Jewish teaching.

The Lord, of course, saw through this scheming and had the seemingly clever young man answer his own question by declaring the answer, based on Jewish teaching in the Torah: “Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy strength, and with all thy mind…”

But that is not the whole answer. There is one more phrase, which does not come from the Torah – “…and thy neighbour as thyself.” This was the Saviour’s own addition to the Old Testament Commandment, showing us that the pharisee had already heard the Lord’s preaching, and was here quoting the Saviour Himself, but this is possibly simple a ruse, so that he can then add, “But who is my neighbour?”

The Jewish answer to the pharisee’s essential question highlights the vast gulf between the consciousness of the Israelites as a people set apart, superior, above and distinct from all other nations, and the new radical challenge of the New Covenant of the Gospel, superceeding the Law: the Old Covenant seeing neighbourly duty and obligation only towards those elect by race, circumcision and Torah… and the New Covenant seeing no distinction between Jew and Gentile, with the opening of the Kingdom of Heaven to all believers.

Christ is clear in this parable that our neighbour may be a person that we have met and encountered for the first time today; is not simply the known and familiar person with whom we feel comfortable and safe; those whom we like and are happy to be with; those who share our views, faith or socio-political outlook; those who speak our language and belong to our ethno-cultural world.

The parable’s initial challenge is that of recognising our neighbour, but we can easily miss the significance of the end of the parable, particularly after the departure of the Samaritan, when the inn becomes the place of healing and recovery, in which care, and acts of mercy and compassion continue at the command of the Samaritan, even though his journey has taken him away. We often fail to recognise this essential detail, and only concentrate on the acts of mercy performed at the road-side.

We should turn to the interprestation of the parable by the Church Fathers to bring us to this point.

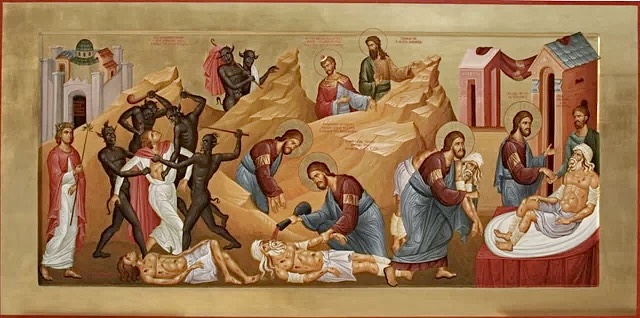

The Church Fathers are very clear that the robbed and beaten man in the parable represents Adam, the first-father – and by extension each and every human being – on that dangerous downward descent from the spiritual heights of Jerusalem to the depths of Jericho, representing rebellion, sin and the passions.

The road which is the place of ambush and attack in the parable is humanity’s perilous downhill journey and spiritual descent that has been rebeliously trodden since the Fall.

The beating and violence inflicted on the unsuspecting victim on this road is understood as that of the demons, attacking and assaulting humanity as it turns its back on spiritual living and obedience to God.

Yet, despite the fact that the victim of the attack in the parable is travelling in a clearly wrong direction of spiritual rebellion and exile, he is not condemned or judged by the Samaritan, the image of Christ the Saviour and Healer, Who like the Samaritans of the Holy Land was an outsider and figure of contempt to the Jewish establishment.

His washing of the victim’s wounds with oil and wine is symbolic of the economy and work of salvation, pointing towards the chrism of the baptismal rite and the oil of unction, and the wine indicative of the Divine Liturgy and the Eucharist.

The representatives of the Old Covenant, the priest and Levite, who had passed on the other side of the road before the arrival of the Samaritan, were not only cold and negligent in their lack of mercy and compassion for the man lying wounded and beaten in his own blood, but were actually symbols of the impotence and powerlessness of the Old Covenant to help or heal fallen humanity.

The Temple, its sacrifices, rites and clergy could do nothing to redeem or heal fallen Adam and his descendents. Their prayers, liturgies and sacrifices were temporary and limited. They could bring no lasting reconciliation between God and man, and heaven and earth. They could bring no lasting forgiveness of sins.

They had no oil and wine as tokens of the healing, redemptive and restorative power of the God-Man we see in the Samaritan. This healing could only come from Him, as the Way, the Truth and the Life.

The Samaritan’s symbolic acts of mercy and compassion in the roadside cleaning of wounds with that self-same oil and wine, and their bandaging, is only the beginning and initiation of the healing process for the man left lifeless as though he were dead

We must contemplate what the Samaritan, representing the Saviour, does next:

“And [he] set him on his own beast, and brought him to an inn, and took care of him. And on the morrow when he departed, he took out two pence, and gave them to the host, and said unto him, Take care of him; and whatsoever thou spendest more, when I come again, I will repay thee.”

As this is a parable, filled with symbolic sigificance, what is the significance of the inn, which is essentially the place of healing, convalescence and restoration for broken, wounded humanity, represented by the bloodied, robbed and beaten man?

The Church Fathers are clear that this is an image of the Church, to which the Saviour entrusts those Whom He has sought out and saved. The Church is the spiritual hospital in which Saviour’s salvific-work continues, and this essentially places responsibility and the work of Christ on each of us, to ensure that the Church, as the household of God, really is a place of spiritual care and healing.

So, when the pharisee asks, “Who is my neighbour?” And the Lord answers with the parable, we are not simply called to recognition of whom our neighbour is by the selfless action of the Samaritan at the roadside, but also by contemplating the inn as the spiritual hospital of the Church, in which each and everyone of us is called to be like the inn-keeper, caring for the wounded, the broken, and the needy, with the Saviour promising us our reward when He comes again.

This places great responsibility on each of us, based on recognition of our neighbour and our willingness and duty to be like the inn-kepper in our care towards those entrusted to us by the Lord, and requiring us to act with love, mercy and compassion: welcoming them and caring for them, in the His Name, not forgetting that the heavenly inheritance spoken of by the pharisee in this parable DEMANDS that we love not only God, but our neighbour.

This is our collective and individual challenge as the Inn of the Church, and when Christ entrusts us with people who are damaged, spiritually or emotionally broken, anxious, fearful and perhaps finding no meaning in earthly life, it is not only our calling, but our God-given duty to be like the inn-keeper to dutifully and solicitously care for them, to bring them to the health and wholeness which Christ brings through salvation and the Grace of the Holy Mysteries.

This was the great labour of St John of Kronstadt, that great inn-keeper treating the bloody, beaten and crippled charges that Christ sent to him in pre-revolutionary St Petersburg – generously caring for the most tragic elements of society: the poorest of the poor, the homeless, orphans and widows, the maimed and disabled, alcoholics, drug addicts, prostitutes and criminals trying to turn around broken and shattered lives.

Like the pharisees, there were those in pre-revolutionary society that looked on with disgust and horror, that St John should take care of these disreputable and sinful outcastes representing the dregs of society. Was not St John bringing the wrong sort of people to the Church, dirtying it by their presence, and driving others away by bringing “the wrong sort of people” to the Church? (Sadly familiar complaints that we have heard with our own ears!)

Yet, the Gospel makes clear that to talk and speculate about whom our neighbour is without accepting the absolute imperative that we MUST love them is to totally miss the point of why the Lord even told this parable.

To love our neighbour is the absolute condition for the heavenly inheritance, and we must love by making the Church a place that is welcoming, loving, merciful and compassionate, in which people feel welcome, secure, safe and wanted.

To refuse to do so, to judge, to exclude, to condemn, to be cold and unwelcoming, to resent the newcomer, to not want “the wrong sort of people” who are different to us, is to actually reject the inheritance of the heavenly kingdom and rebeliously reject the Saviour’s words.

We are not the Old Israel, superior, set apart, and above all nations. We are the New Israel making no differentiation according to race and language, baptising all men and women in the Name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, preaching and declaring the Kingdom of Heaven to all believers, and welcoming all who hear the words of Christ, “Come unto me, all ye that labour and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest”, not only offering – in His Name – a place of rest, but also a place of spiritual healing and restoration, caring for them as those whom the Great Samaritan has brought to us, saying, “Take care of him”.

As the Church and household of Faith, and Christ’s spiritual hospital, let us do so with gladness, compassion and mercy, loving and recognising our neighbour, in obedience to the Saviour of our souls, Who will reward us when He comes again.

Amen!